The past week in Türkiye has been full of loud statements and news from the diplomatic front.

The world was rocked by the news of the death of Queen Elizabeth II, and it also sparked considerable discussions in the Turkish media. And it was not about philological battles over the correct spelling of the new British monarch’s name. Despite the lack of a “ch” in the Turkish language, Turkish pragmatism allowed the issue to be resolved without too much debate - retaining the unique transliteration of the name Charles III.

But it didn’t go with no debates at all. Tireless searchers for the conspiracy theories and just conspiracy fans (they are an integral part of the thinking and political culture of the Turkish society) have managed to find a link between the death of Elizabeth II and the former Turkish President Abdullah Gül being in London at the same time. Despite the fact that Gül’s Twitter account has photos of him attending the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies event on the same day, the coincidence was enough to once again remind Turkish citizens that one of the candidates for the status of a united opposition candidate in the upcoming 2023 presidential elections is an agent of British influence and has close ties to the royal family.

Anadolu Agency

These allegations are not new. Many people in the country still believe that the British Queen’s historic visit to Türkiye back in 2008 was intended to enhance not only international prestige but also the internal political positions of the then newly elected 11th President. Abdullah Gül’s successful reciprocal visit to London in 2011, as well as his receiving the Chatham House Statesman of the Year Award by the Queen in 2010, have only confirmed these suspicions.

The excessive attention towards the former president, as well as the campaign to discredit him in the Turkish media, is linked not least to another round of internal “primaries” for the so-called “opposition bloc of six” - a broad coalition of parties that will present a common front against the current government in the next elections in 2023. Experts are talking more and more about the possibility of early elections already this autumn, which many people believe could save Erdoğan's government from a further drop in the ratings and at the same time deprive the time for the opposition to consolidate their efforts and choose a single candidate.

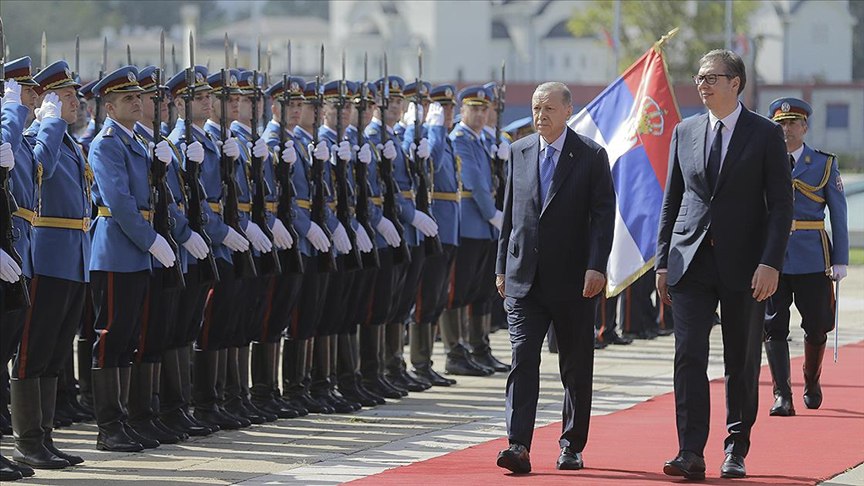

At exactly such a background of the election campaign - the growing polarisation of society, anti-Western sentiment and conspiracy paranoia - the resonant statements of current President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at the recent press conferences in Serbia and Croatia, in which he in fact reproduced Russian narratives, should be seen.

Anadolu Agency

“Western policy towards Russia is built on provocations”; “European sanctions are to blame for the gas crisis”; “Ukrainian grain does not go to the world's poorest countries, but to the rich and developed ones”; “there are no winners in the Russia-Ukraine war, everyone will lose”; "Russia is a state which cannot be underestimated”... If it was not for the video, one would think that these theses were from the speech of the Russian president, not Turkish.

The rhetoric of both leaders of “the states of two continents” towards the West is getting closer, despite the fact that Türkiye is a member of NATO and Russia is defined by the new Alliance strategy as "the most serious and immediate threat to the security of allies, as well as to the peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area".

However, from the Eurasian space, threats to peace, security and stability look different. For Türkiye, NATO’s “eastern flank” is not washed by the waters of the Baltic Sea, but by the Mediterranean. Hence, in the perception of the Turkish military and political elites, the key security threats come from the borders of Syria, not Russia. More precisely, the border territories that are controlled by Kurdish militias armed by the US and other Ankara’s alliance partners.

It is this “regional vision” of peace that unites Ankara and Moscow in their search for a new, “fairer” world order. Not only Putin but also Erdoğan believes that the time of unilateral Western domination led by the US is over and that the international system needs a new order that takes into account the interests of the powerful regional states.

Officially, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKR) has never abandoned Türkiye’s European or Euro-Atlantic path, although the country is increasingly veering in the opposite direction amid problems in the relationships with the US and EU. By maintaining its NATO membership as leverage over its partners, both Western and Eastern, Ankara is trying to achieve greater “strategic autonomy” in a region that is gaining importance in the “post-Western” world order. On the one hand, this allows for a much looser interpretation of the country’s NATO commitments and to be guided primarily by its own interests in dealing with regional policy and national security issues. On the other hand, anti-Western rhetoric helps the ruling coalition to mobilise an electoral base and gain broad support from the population, often playing into the opposition’s field.

Experts have already dubbed this search for “autonomy” from Western allies and the constant balancing between different Eurasian and Transatlantic camps in the face of growing geopolitical competition “in the particular path of the new Türkiye. Although the Turkish authorities traditionally present Turkish-Russian rapprochement as an illustration of the benefits of multi-vectorism, in reality, this “independent” foreign policy only increases Türkiye’s dependence on Russia. The use of Montreux Convention restrictions to block access to the Black Sea for NATO ships, anti-Western rhetoric and accusations of the US and NATO countries of fomenting regional conflicts, discussions about the benefits of SCO and BRICS membership actually play in Moscow’s favour. At the same time, Türkiye’s desire to find “regional solutions to the regional problems” limits the scope for cooperation with NATO and opens the way to alternative coordination mechanisms with Russia and Iran (such as the Astana Platform for Syria or the 3+3 format for the South Caucasus), drawing Ankara into Eurasian projects and distancing it from the Western partners. The Türkiye’s dependence on the Russian energy resources, markets, tourists and cheap money of sub-sanctioned Russian oligarchs only adds to the overall picture of asymmetric partnership.

The AKR’s junior coalition partner, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), holds ideologically similar views. Although MHP supporters are more critical of Russia and often view it as a direct competitor for influence in the Caucasus and Central Asia, the party leadership rarely speaks of the Kremlin’s genocidal policies and repression of the Turkic and Muslim communities both in the Russian “Federation” itself and in the occupied territories of Ukraine and Georgia. Just as the Turkish pragmatism prevents the authorities from taking a clear and consistent position on the Uyghur question in relationships with China, Russia’s gross violations of the rights of Crimean Tatars, Meskhetian Turks, Chechens, Circassians and other kindred communities cannot outweigh the economic benefits of cooperation with Moscow. Consequently, even the most radical nationalists are happy to repeat the anti-American mantras of Russian propaganda, while remaining silent about Russia’s crimes.

In this sense, the definitive Kremlin’s aggression against Ukraine was a litmus test, revealing not always obvious sentiments in Turkish society - distrust of the West, economic dependence on Russia, broad public support for Ankara’s official policy of neutrality and balancing between Kyiv and Moscow.

A recent study by the German think tank SWP on the Turks’ perceptions of the war in Ukraine provides interesting examples of how “Türkiye’s rebellion against the West” is becoming a common theme for different players in the ruling coalition. For example, MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli puts responsibility for the “Ukrainian crisis” not only on “Russian aggression” but also on “provocations by NATO and Western countries”. By claiming that Türkiye “should not sacrifice its relationships with friendly countries and neighbours” and that it would “neither be a frontline state” nor “would go to war on behalf of the West”, Bahçeli is solving two tasks at once. On one hand, he is crushingly criticising the traditional enemies of the Turkish nationalists - the US and NATO. On the other, he is feeding his own electorate’s dreams of a return to the Caucasus and preventing Western domination of the resource-rich region of Central Asia.

At the same time, Ankara is well aware that Russia remains Turkey’s main competitor not only in the Black Sea region but also in the Mediterranean. Consequently, the supply of "bayraktars" to the ZSU (the Armed Forces of Ukraine) and the closure of the Straits to the Russian warships from entering the waters of the occupied Crimea and the Russian bases in Syria, correspond not only to the spirit of the strategic partnership with Kyiv but also to Türkiye’s own interests.

Therefore, whatever the pre-election manoeuvres of the Turkish government, its course on Ukraine will invariably be based on three key principles:

(1) political support and military-technical cooperation with Kyiv as a counterweight to Russian dominance in the region;

(2) developing trade, economic and energy cooperation with Moscow as a pledge for Türkiye’s domestic political stability;

(3) balancing Russia and the West as a way to strengthen its own position on the international stage.

Whereas Ukraine has limited influence on the latter two factors, Ankara’s interest in cooperation in the DIC and Ankara's well-known Turkish pragmatism give it every chance of developing mutually advantageous relationships with a clear focus on its own national interests. The question is whether we will be able to make the best use of them.

*UA South does not edit the texts of blogs and is not responsible for their content. The opinions of the authors of publications may not coincide with the position of the editors.

Türkiye-2023: what to expect for Ukraine? (Part 1)